Tutorial#

1. Basics#

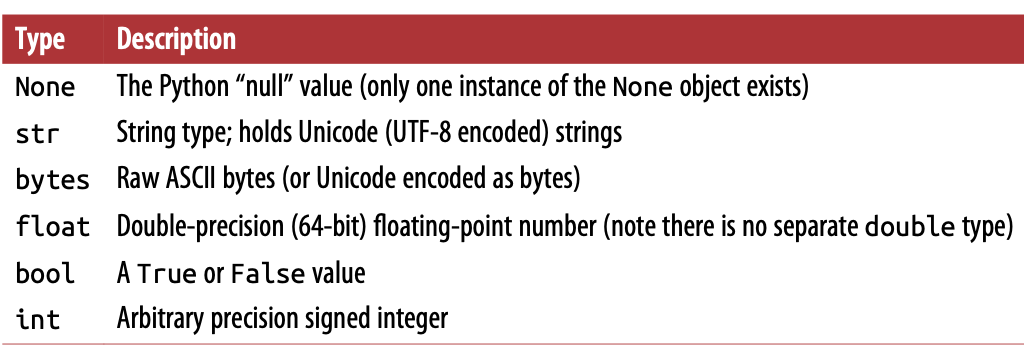

1.1. Variables and Types#

Identify the types(Duck typing)

#i.e. Test whether it's iterable.

def isiterable(obj):

try:

iter(obj)

return True

except TypeError: #not iterable

return False

Numbers#

\(\left\{ \begin{aligned} &Integers(whole number)\longrightarrow int(x) \text{ x converted to integer}\\\\ &Floats(decimals)\longrightarrow float(x)\text{ x converted to float} \end{aligned} \right.\)

Boolean Type#

\(\left\{ \begin{aligned} &True\\ &False \end{aligned} \right.\)

bool is a subclass of int (see Numeric Types — int, float, complex). In many numeric contexts, False and True behave like the integers 0 and 1, respectively. However, relying on this is discouraged; explicitly convert using int() instead.

Sequence Types#

\(\left\{ \begin{aligned} &list\\ &tuple\\ &range\end{aligned} \right.\)

Operation |

Result |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

the concatenation of s and t |

|

equivalent to adding s to itself n times |

|

ith item of s, origin 0 |

|

slice of s from i to j |

|

slice of s from i to j with step k |

|

length of s |

|

smallest item of s |

|

largest item of s |

|

index of the first occurrence of x in s (at or after index i and before index j) |

|

total number of occurrences of x in s |

list

Lists are mutable sequences, typically used to store collections of homogeneous items

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

#list can be mutable

my_list.append(4) # my_list is now [1, 2, 3, 4]

my_list.remove(2) # my_list is now [1, 3, 4]

tuple

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

my_tuple.count(2) # Returns the count of number 2 in the tuple

my_tuple.index(3) # Returns the index of number 3 in the tuple

ranges

The range type represents an immutable sequence of numbers and is commonly used for looping a specific number of times in for loops.

start

The value of the start parameter (or

0if the parameter was not supplied)stop

The value of the stop parameter

step

The value of the step parameter (or

1if the parameter was not supplied)

range(0,20,2)

range produces integers up to but not including the endpoint. A common use of range is for iterating through sequences by index:

seq = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for i in range(len(seq)):

val = seq[i]

Text sequence types—str#

You can write string literals using either single quotes ’ or double quotes “:

a = 'one way of writing a string'

b = "another way"

For multiline strings with line breaks, you can use triple quotes, either ‘’’ or “””:

c = """

This is a longer string that

spans multiple lines

"""

Strings are a sequence of Unicode characters and therefore can be treated like other sequences, such as lists and tuples

In [64]: s = 'python'

In [65]: list(s)

Out[65]: ['p', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n']

In [66]: s[:3]

Out[66]: 'pyt'

None#

None is the Python null value type. If a function does not explicitly return a value, it implicitly returns None:

In [97]: a = None In [98]: a **is** None

Out[98]: True

In [99]: b = 5

In [100]: b is not None

Out[100]: True

None is also a common default value for function arguments:

def add_and_maybe_multiply(a, b, c=None):

result = a + b

if c is not None:

result = result *c

return result

dict#

A mapping object maps hashable values to arbitrary objects. Mappings are mutable objects. There is currently only one standard mapping type, the dictionary.

Use a comma-separated list of

key: valuepairs within braces:{'jack': 4098, 'sjoerd':4127}or{4098: 'jack', 4127: 'sjoerd'}

dishes = {'eggs': 2, 'sausage': 1, 'bacon': 1, 'spam': 500}

keys = dishes.keys()

values = dishes.values()

a = dict(one=1, two=2, three=3)

b = {'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'three': 3}

c = dict(zip(['one', 'two', 'three'], [1, 2, 3]))

d = dict([('two', 2), ('one', 1), ('three', 3)])

e = dict({'three': 3, 'one': 1, 'two': 2})

f = dict({'one': 1, 'three': 3}, two=2)

a == b == c == d == e == f

True

2. Control Flow#

2.1. if, elif, and else#

An if statement can be optionally followed by one or more elif blocks and a catch- all else block if all of the conditions are False:

if x < 0:

print('It's negative')

elif x == 0:

print('Equal to zero')

elif 0 < x < 5:

print('Positive but smaller than 5')

else:

print('Positive and larger than or equal to 5')

2.2. for loops#

for loops are for iterating over a collection (like a list or tuple) or an iterater.

continue

You can advance a for loop to the next iteration, skipping the remainder of the block, using the continue keyword.

# Example for the continue keys used in loop,sums up integers in a list and skips None values:

sequence = [1, 2, None, 4, None, 5]

total=0

for value in sequence:

if value is None:

continue

total+=value

break

A for loop can be exited altogether with the break keyword.

# Example for the break keys used in the loop,this code sums elements of the list until a 5 is reached:

sequence = [1, 2, 0, 4, 6, 5, 2, 1]

total=5

for value in sequence:

if value==5:

break

total+=value

2.3. while loops#

A while loop specifies a condition and a block of code that is to be executed until the condition evaluates to False or the loop is explicitly ended with break:

x = 256;total = 0

while x > 0:

if total > 500:

break

total += x

x = x // 2

2.4. pass#

pass is the “no-op” statement in Python. It can be used in blocks where no action is to be taken (or as a placeholder for code not yet implemented); it is only required because Python uses whitespace to delimit blocks:

if x < 0:

print('negative!')

elif x == 0:

# TODO: put something smart here pass

else:

print('positive!')

3. Functions#

Functions are the primary and most important method of code organization and reuse in Python. As a rule of thumb, if you anticipate needing to repeat the same or very similar code more than once, it may be worth writing a reusable function. Functions can also help make your code more readable by giving a name to a group of Python statements.

Functions are declared with the def keyword and returned from with the return key word:

def my_function(x, y, z=1.5):

if z > 1:

return z * (x + y)

else:

return z / (x + y)

There is no issue with having multiple return statements. If Python reaches the end of a function without encountering a return statement, None is returned automatically.

Each function can have positional arguments and keyword arguments. Keyword arguments are most commonly used to specify default values or optional arguments. In the preceding function, x and y are positional arguments while z is a keyword argu‐ ment. This means that the function can be called in any of these ways:

my_function(5, 6, z=0.7)

my_function(3.14, 7, 3.5)

my_function(10, 20)

\(\left\{\begin{aligned}&positional \quad arguments\rightarrow\text{cannot change order}\\ &keyword\quad arguments\rightarrow \text{can change order}\end{aligned}\right.\)

3.1. Namespaces, Scope, and Local Functions#

Functions can access variables in two different scopes: global and local. An alternative and more descriptive name describing a variable scope in Python is a namespace.

Any variables that are assigned within a function by default are assigned to the local namespace.

def func():

a = []

for i in range(5):

a.append(i)

Assigning variables outside of the function’s scope is possible, but those variables must be declared as global via the global keyword:

a = None

def bind_a_variable():

global a

a=[]

bind_a_variable()

print(a)

Discourage use of the global keyword. Typically global variables are used to store some kind of state in a system. If you find yourself using a lot of them, it may indicate a need for object- oriented programming (using classes).

3.2. Anonymous (Lambda) Functions#

Python has support for so-called anonymous or lambda functions, which are a way of writing functions consisting of a single statement, the result of which is the return value. They are defined with the lambda keyword。

def short_function(x):

return x * 2

# The anonymous function of the one above.

equiv_anon = lambda x: x*2

# One reason lambda functions are called anonymous functions is that , unlike functions declared with the def keyword, the function object itself is never given an explicit __name__ attribute.

3.3. Errors and Exception Handling#

#The code in the except part of the block will only be executed if float(x) raises an exception:

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except:

return x

You might want to only suppress ValueError, since a TypeError (the input was not a string or numeric value) might indicate a legitimate bug in your program. To do that, write the exception type after except:

#You can catch multiple exception types by writing a tuple of exception types instead(the parentheses are required):

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except (TypeError, ValueError):

return x

In some cases, you may not want to suppress an exception, but you want some code to be executed regardless of whether the code in the try block succeeds or not. To do this, use finally:

f=open(path,'w')

try:

write_to_file(f)

finally:

f.close()

Here, the file handle f will always get closed. Similarly, you can have code that executes only if the try: block succeeds using else:

f=open(path,'w')

try:

write_to_file(f)

except:

print('Failed')

else:

print('Succeeded')

finally:

f.close()

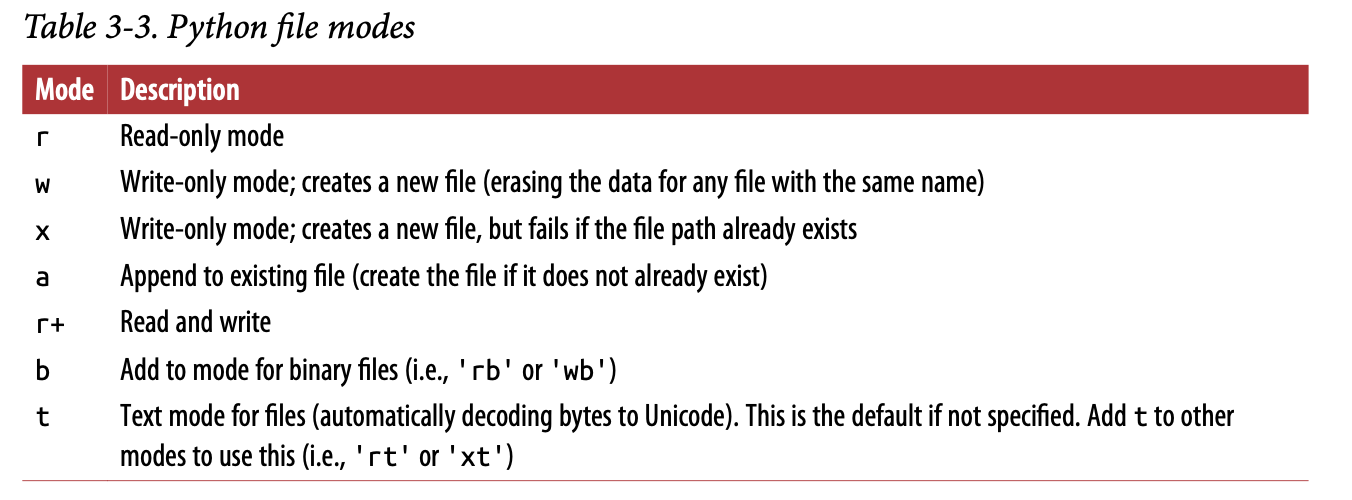

3.4. Files and the Operating System#

Although most of the time we read data files from disk to the Python data structure is using pandas library such as pd.read_csv() .It’s important to understand the basics of how to work with files in Python.

To open a file for reading or writing, use the built-in open function with either a rela‐ tive or absolute file path:

path = 'examples/segismundo.txt'

f = open(path)

# By default, the file is opened in read-only mode 'r'. We can then treat the file handle f like a list and iterate over the lines like so:

for line in f:

pass

The lines come out of the file with the end-of-line (EOL) markers intact, so you’ll often see code to get an EOL-free list of lines in a file like:

lines = [x.rstrip() for x in open(path)]

lines

#output:['Sueña el rico en su riqueza,','que más cuidados le ofrece;','','sueña el pobre que padece','su miseria y su pobreza;','','sueña el que a medrar empieza,','sueña el que afana y pretende,','sueña el que agravia y ofende,','','y en el mundo, en conclusión,','todos sueñan lo que son,','aunque ninguno lo entiende.','']

f.close()

When you use open to create file objects, it is important to explicitly close the file when you are finished with it. Closing the file releases its resources back to the operating system:

3.5. Class#

Objects are an encapsulation of variables and functions into a single entity. Objects get their variables and functions from classes. Classes are essentially a template to create your objects.